An accessibility statement is one of those pages most teams don’t think about until something forces the issue. A user hits a blocker and asks for help. A procurement review wants proof of process. Or someone internally asks the question no one loves answering: “What can we honestly say about accessibility right now?”

If you already work with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), you know the hard part isn’t writing a few well-meaning lines. It’s making sure the statement matches the lived experience of your site. It needs to be specific enough to help someone plan their next step, careful enough to hold up under scrutiny, and practical enough that it won’t be outdated after the next release.

We’ll walk through the common versions you’ll see online, what they communicate at a glance, and what to include if you want a statement that stays accurate as your site and your workflows keep evolving.

Accessibility Statement Best Practices

WCAG does not require an accessibility statement. That surprises a lot of teams. But “not required” and “not important” are two different things.

A statement helps people understand what to expect and how to get support. It also helps internal teams because it forces clarity. If it feels hard to explain your testing process or your goals, that usually points to a bigger issue. The work may be happening in pieces, but the process is not fully owned yet.

In some cases, publishing a statement is not optional. The Revised Section 508 Standards in the United States apply to many public institutions and require accessibility statements that follow a specific format. And even when an organization is not under Section 508, laws and regulations like the ADA, AODA, or EAA raise the stakes around access and transparency.

There is also a practical reality. When a complaint or demand letter happens, this page gets read. Often early. It shows what you claimed, what you promised, and whether your wording matches the experience. So it is not only communication. It can become evidence.

Missing Accessibility Statement: User and Risk Impact

No page. No link. No mention in the footer or on the contact page.

When a site has no accessibility statement, users are left guessing. If they hit a barrier, they also have no clear way to report it. Many people will not spend extra time searching for a hidden email address. They will leave.

A missing statement usually points to one of three situations:

- Accessibility has not been considered yet.

- It has been considered, but it keeps getting pushed down the list.

- Work is happening, but nobody has taken ownership of communicating it.

None of that helps someone trying to apply for a job, schedule an appointment, pay a bill, or place an order.

It can also create risk. It can look like there is no accessibility process at all. Again, that is not proof by itself. But it is not a good signal.

Boilerplate Accessibility Statement: Copy, Paste, Risk

Boilerplate is easy to spot. It often says “we are committed to accessibility” and references WCAG, but nothing else. No date. No testing details. No contact method that feels monitored. Sometimes it even claims full compliance.

This version is risky for a simple reason. It makes a promise without support.

If the site still has keyboard traps, broken form labels, missing focus states, or confusing headings, users will notice the mismatch right away. The page that was meant to build confidence does the opposite.

Boilerplate also tends to sound the same across many sites. That sameness can read as performative. People have seen it before, and many have learned it does not mean much in practice.

If your statement came from a template, treat it as a draft. It should be reviewed with the same care you would give a checkout flow, an account login, or a support page.

Aspirational Accessibility Statement: Nice Words, Few Details

This one is tricky because it can come from a good place.

Aspirational statements often sound warm and well-intentioned. They talk about inclusion, values, and long-term goals. Some mention employee groups, empathy workshops, or automated tools. The problem isn’t the heart behind it. It’s that none of this helps a user complete a task today.

Where these statements tend to fall short is in clarity. They describe the why but skip the what now. Users trying to pay a bill or submit a form need concrete information, not broad promises about the future. When a statement avoids specifics about testing, current site limitations, or how to get help, it becomes more of a brand message than a resource.

This is also where teams can unintentionally stall. Publishing a warm, values-driven accessibility statement can create the illusion that the work is “handled,” even when the practical steps are still ahead.

How to Write a Good Accessibility Statement

A strong accessibility statement is simple in a practical way. It does not try to sound impressive. It explains what you are doing, what you know, and how users can reach you if they run into a problem.

You can think of it as having a few main ingredients. The exact recipe will vary by organization, but these parts show up again and again in statements that users actually trust.

Purpose and Commitment

Start with a clear handshake. Say you are dedicated to making your website or content accessible, including for people who use assistive technology. Keep it short and human. It should feel like support, not legal language.

Standards and Guidelines (WCAG)

Mention the standard you are aiming for, such as WCAG 2.2 Level AA. If that is your target, say it. If you are still working toward it, you can say that too. Honesty here builds more trust than a bold claim.

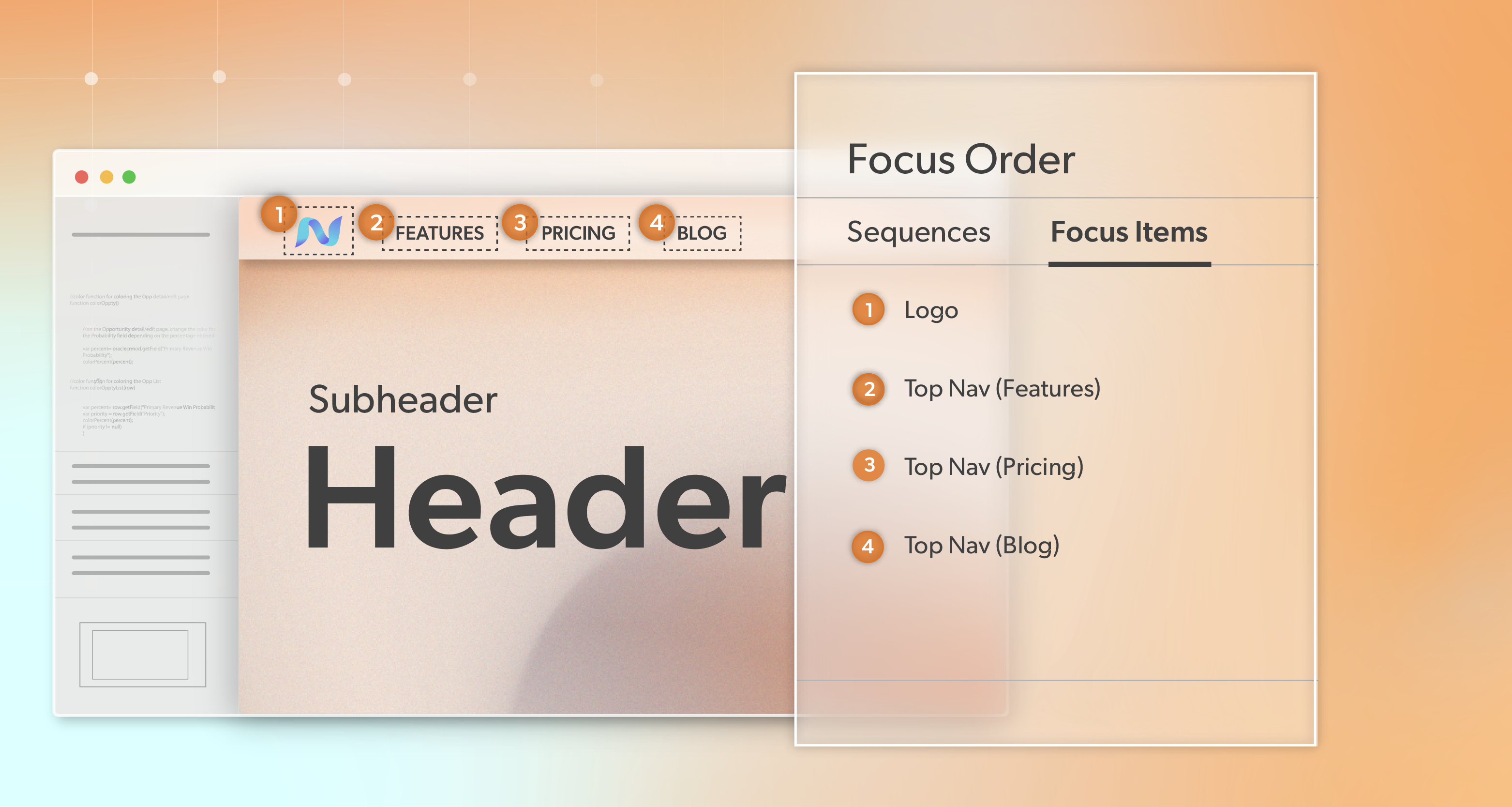

Testing Approach and Review Dates

This is where you move from “we care” to “we have a process.”

Include:

- The date of your last accessibility evaluation

- Whether you used automated checks, manual testing, or both

- How often you plan to review the site again

You can also name what you focus on at a high level, like key user flows, forms, templates, and shared components. Users do not need a lab report. They do need to know that testing is not a rumor.

Areas of Success

This part is often missing, but it helps. Call out what is working well today. It tells users where the experience is likely to be smoother, and it shows that accessibility work is not only future tense.

Examples might include:

- Core navigation and main templates reviewed for keyboard and screen reader use

- Improved form labels and clearer error handling in key workflows

- Updates to contrast and focus styling on shared components

Keep this realistic. Don’t oversell. Just help users understand where the site is in better shape.

Areas Needing Improvement

Nobody’s site is perfect, and users already know that. The question is whether you are willing to be honest about it.

List the known problem areas that affect tasks. For example:

- Older pages that still have heading or label issues

- Some PDFs or documents that are not fully accessible yet

- Third-party tools that have accessibility limits, you are working to address

If you can add timelines or priority windows, do it. Avoid vague “we’re working on it” language. A specific window builds confidence because it shows this is planned work, not wishful thinking.

Assistive Technology and Environments Tested

Mention the kinds of environments you consider, such as desktop and mobile, keyboard-only use, and screen readers. A short list helps users understand whether your testing reflects their reality.

Contact Information and Support Process

Provide an easy way to reach out if someone runs into a barrier. Email is a baseline. Some teams also offer a phone number or an accessible form.

Just as important, include a brief note about what happens after someone reaches out. Even one sentence helps. For example, reports are reviewed and routed to the right team.

Where to Place the Accessibility Statement Link

Make sure the statement is easy to find. Put it in the footer, and consider linking it from the contact page as well. If users need a search engine to find it, you are adding friction at the exact moment they need support.

Common Accessibility Statement Mistakes

Even a well-meaning statement can miss the mark. These are the mistakes that show up the most.

Overly Legal or Technical Language

An accessibility statement is not a compliance brief. Write for people. Define acronyms. Use short paragraphs and lists. Make it scannable.

Claims You Can’t Support

Avoid saying “fully compliant” unless you can back it up and keep it true over time. Websites change constantly. A claim that was accurate once can become inaccurate fast.

A safer approach is to describe your goal, your testing, and your process.

No Clear Feedback Path

If there is no clear way to report barriers, the statement fails one of its most important jobs. And if you list an email address, make sure it is monitored.

Burying the Accessibility Statement

Put it somewhere consistent, like a global footer. Users should not have to hunt.

Make Your Accessibility Statement Match Reality

An accessibility statement only does its job if it stays close to reality. As your site changes, the statement should keep pace, reflecting what has been tested, what still needs attention, and how people can reach you when something doesn’t work as expected. If reading your current statement feels uncomfortable or outdated, that’s not a dead end. It’s a useful signal that your process needs clearer ownership, stronger testing language, or a better plan for keeping the page current.

At 216digital, our team is committed to helping you take the steps towards web accessibility on your terms by developing a strategy to integrate WCAG 2.2 compliance into your development roadmap. We offer comprehensive services that not only audit your website for accessibility but also provide solutions to meet ADA compliance requirements.

To learn what more you should do to achieve and maintain accessibility for your team, schedule a Complimentary ADA Strategy Briefing with the experts at 216digital.