A form can succeed or fail based on how predictable its validation and recovery patterns are. When users can’t understand what the form expects or how to correct an issue, the flow breaks down, and small problems turn into dropped sessions and support requests. The reliable approach isn’t complex—it’s consistent: clear expectations, helpful correction paths, and markup that assistive technologies can interpret without ambiguity. That consistency is the foundation of accessible form validation.

Two ideas keep teams focused:

- Validation is the contract. These are the rules the system enforces.

- Error recovery is the experience. This is how you help users get back on track.

You are not “showing error messages.” You are building a recovery flow that answers three questions every time:

- Do users notice there is a problem?

- Can they reach the fields that need attention without hunting?

- Can they fix issues and resubmit without getting stuck in friction loops?

Accessible Form Validation Begins on the Server

Server-side validation is not optional. Client-side code can be disabled, blocked by security policies, broken by script errors, or bypassed by custom clients and direct API calls. The server is the only layer that stays dependable in all of those situations.

Your baseline should look like this:

- A

<form>element that can submit without JavaScript. - A server path that validates and re-renders with field-level errors.

- Client-side validation layered in as an enhancement for speed and clarity.

A minimal baseline:

<form action="/checkout" method="post">

<!-- fields -->

<button type="submit">Continue</button>

</form>From there, enhance. Client-side validation is a performance and usability layer (fewer round-trips, faster fixes), but it cannot become the source of truth. In code review terms: if disabling JavaScript makes the form unusable, the architecture is upside down.

Once submission is resilient, you can prevent a large share of errors by tightening the form itself. This foundation keeps your accessible form validation stable even before you begin adding enhancements.

Make the Form Hard to Misunderstand

Many “user errors” are design and implementation gaps with a different label. Prevention starts with intent that is clear during keyboard navigation and screen reader use.

Labels That Do Real Work

Every control needs a programmatic label:

<label for="email">Email address</label>

<input id="email" name="email" type="email">Avoid shifting meaning into placeholders. Placeholders disappear on focus and do not behave as labels for assistive technology. If a field is required or has a format expectation, surface that information where it will be encountered during navigation:

<label for="postal">

ZIP code <span class="required">(required, 5 digits)</span>

</label>

<input id="postal" name="postal" inputmode="numeric">This supports basic expectations in WCAG 3.3.2 (Labels or Instructions): users can understand what is needed before they submit.

Group Related Inputs

For radio groups, checkbox groups, or multi-part questions, use fieldset + legend so the “question + options” relationship is explicit:

<fieldset>

<legend>Contact preference</legend>

<label>

<input type="radio" name="contact" value="email">

Email

</label>

<label>

<input type="radio" name="contact" value="sms">

Text message

</label>

</fieldset>This prevents the common failure where options are read out as a scattered list with no shared context. Screen reader users hear the question and the choices as one unit.

Use the Platform

Choose appropriate input types (email, tel, number, date) to use built-in browser behavior and reduce formatting burden. Normalize on the server instead of making users guess the system’s internal rules:

- Strip spaces and dashes from phone numbers.

- Accept

12345-6789, but store12345-6789or123456789consistently. - Accept lowercase, uppercase, and mixed-case email addresses; normalize to lowercase.

The more variation you handle server-side, the fewer opaque errors users see.

Don’t Hide Labels Casually

“Visual-only” placeholders and icon-only fields might look clean in a mock-up, but they:

- Remove a click/tap target that users rely on.

- Make it harder for screen reader users to understand the field.

- This leads to guessing when someone returns to a field later.

If you absolutely must visually hide a label, use a visually-hidden technique that keeps it in the accessibility tree and preserves the click target.

You’ll still have errors, of course—but now they’re about the user’s input, not your form’s ambiguity.

Write Error Messages That Move Someone Forward

An error state is only useful if it helps someone correct the problem. Rules that hold up well in production:

- Describe the problem in text, not just color or icons.

- Whenever possible, include instructions for fixing it.

Instead of: Invalid input

Try: ZIP code must be 5 digits.

Instead of:Enter a valid email

Try: Enter an email in the format name@example.com.

A practical markup pattern is a reusable message container per field:

<label for="postal">ZIP code</label>

<input id="postal" name="postal" inputmode="numeric">

<p id="postalHint" class="hint" hidden>

ZIP code must be 5 digits.

</p>When invalid, show the message and mark the control:

<input id="postal"

name="postal"

inputmode="numeric"

aria-invalid="true"

aria-describedby="postalHint">Visually, use styling to reinforce the error state. Semantically, the combination of text and state is what makes it usable across assistive technologies. Clear, actionable messages are one of the most reliable anchors of accessible form validation, especially when fields depend on precise formats.

With messages in place, your next decision is the presentation pattern.

Pick an Error Pattern That Matches the Form

There is no universal “best” pattern. The decision should reflect how many errors are likely, how long the form is, and how users move through it. Choosing the right pattern is one of the most important decisions in accessible form validation because it shapes how people recover from mistakes.

Pattern A: Alert, Then Focus (Serial Fixing)

Best for short forms (login, simple contact form) where one issue at a time makes sense.

High-level behavior:

- On submit, validate.

- If there’s an error, announce it in a live region.

- Mark the field as invalid and move focus there.

Example (simplified login form):

<form id="login" action="/login" method="post" novalidate>

<label for="username">Username</label>

<input id="username" name="username" type="text">

<div id="usernameHint" class="hint" hidden>

Username is required.

</div>

<label for="password">Password</label>

<input id="password" name="password" type="password">

<div id="passwordHint" class="hint" hidden>

Password is required.

</div>

<div id="message" aria-live="assertive"></div>

<button type="submit">Sign in</button>

</form>

<script>

const form = document.getElementById("login");

const live = document.getElementById("message");

function invalidate(fieldId, hintId, announcement) {

const field = document.getElementById(fieldId);

const hint = document.getElementById(hintId);

hint.hidden = false;

field.setAttribute("aria-invalid", "true");

field.setAttribute("aria-describedby", hintId);

live.textContent = announcement;

field.focus();

}

function reset(fieldId, hintId) {

const field = document.getElementById(fieldId);

const hint = document.getElementById(hintId);

hint.hidden = true;

field.removeAttribute("aria-invalid");

field.removeAttribute("aria-describedby");

}

form.addEventListener("submit", (event) => {

reset("username", "usernameHint");

reset("password", "passwordHint");

live.textContent = "";

const username = document.getElementById("username").value.trim();

const password = document.getElementById("password").value;

if (!username) {

event.preventDefault();

invalidate("username", "usernameHint",

"Your form has errors. Username is required.");

return;

}

if (!password) {

event.preventDefault();

invalidate("password", "passwordHint",

"Your form has errors. Password is required.");

return;

}

});

</script>Tradeoff: On longer forms, this can feel like “whack-a-mole” as you bounce from one error to the next.

Pattern B: Summary at the Top (Errors on Top)

Best when multiple fields can fail at once (checkout, account, applications). Behavior:

- Validate all fields on submit.

- Build a summary with links to each failing field.

- Move the focus to the summary.

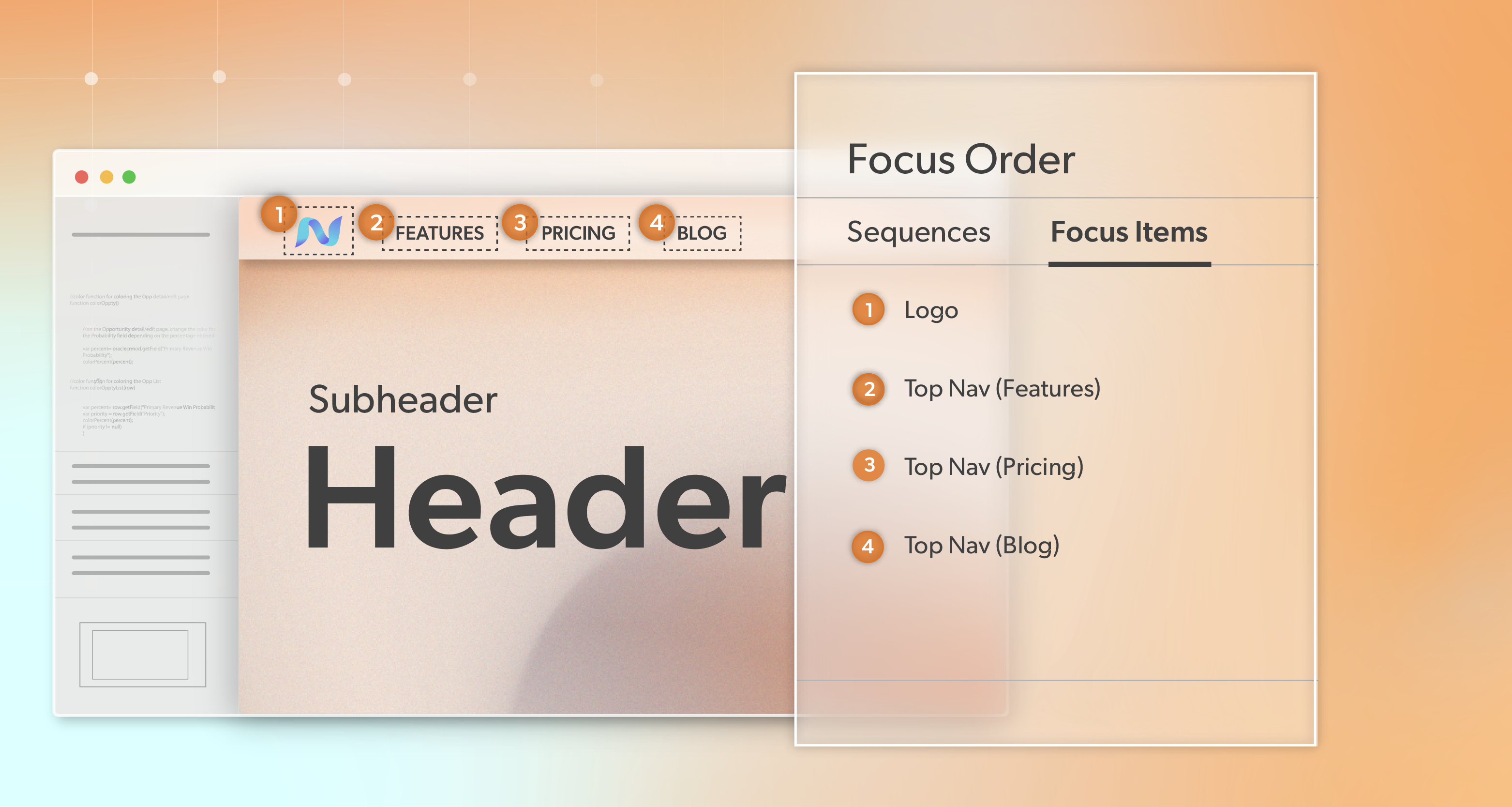

This reduces scanning and gives users a clear plan. It also mirrors how many people naturally work through a list: top to bottom, one item at a time. When built with proper linking and focus, this supports WCAG 2.4.3 (Focus Order) and 3.3.1 (Error Identification).

Pattern C: Inline Errors

Best for keeping the problem and the fix in the same visual area. Behavior:

- Show errors next to the relevant control.

- Associate them programmatically with

aria-describedby(oraria-errormessage) and mark invalid state.

On its own, inline-only can be hard to scan on long forms. The sweet spot for accessible form validation is often:

Summary + inline

A summary for orientation, inline hints for precision.

Make Errors Machine-Readable: State, Relationships, Announcements

Recovery patterns only help if assistive technology can detect what changed and why. This pattern also matches key WCAG form requirements, which call for clear states, programmatic relationships, and perceivable status updates.

1) State: Mark Invalid Fields

Use aria-invalid="true" for failing controls so screen readers announce “invalid” on focus. This gives immediate feedback without extra navigation.

2) Relationships: Connect Fields to Messages

Use aria-describedby (or aria-errormessage) so the error text is read when the user reaches the field. If a field already has help text, append the error ID rather than overwriting it. This is a common regression point in component refactors.

<input id="email"

name="email"

type="email"

aria-describedby="emailHelp emailHint">This approach makes sure users hear both the help and the error instead of losing one when the other is added.

3) Announcements: Form-Level Status

Use a live region to announce that submission failed without forcing a focus jump just to discover that something went wrong:

<div id="formStatus" aria-live="assertive"></div>Then, on submit, set text like: “Your form has errors. Please review the list of problems.”

Someone using a screen reader does not have to guess whether the form was submitted, failed, or refreshed. They hear an immediate status update and can move to the summary or fields as needed.

Use Client-Side Validation as a Precision Tool (Without Noise)

Once semantics and recovery are solid, client-side validation can help users move faster—so long as it does not flood them with interruptions.

Guidelines that tend to hold up in production:

- Validate on submit as the baseline behavior.

- Use live checks only when they prevent repeated failures (complex password rules, rate-limited or expensive server checks).

- Prefer “on blur” or debounced validation instead of firing announcements on every keystroke.

- Avoid live region chatter. If assistive tech is announcing updates continuously while someone types, the form is competing with the user.

Handled this way, accessible form validation supports the person filling the form instead of adding cognitive load.

Define “Done” Like You Mean It

For high-stakes submissions (financial, legal, data-modifying), error recovery is not the whole job. Prevention and confirmation matter just as much:

- Review steps before final commit.

- Confirmation patterns where changes are hard to reverse.

- Clear success states that confirm completion.

Then keep a test plan that fits into your workflow:

- Keyboard-only: complete → submit → land on errors → fix → resubmit.

- Screen reader spot check: “invalid” is exposed, error text is read on focus, form-level status is announced.

- Visual checks: no color-only errors, focus is visible, zoom does not break message association.

- Regression rule: validation logic changes trigger recovery-flow retesting.

Teams that fold these checks into their release process see fewer “the form just eats my data” support tickets and have a clearer path when regression bugs surface.

Bringing WCAG Error Patterns Into Your Production Forms

When teams treat error recovery as a first-class experience, forms stop feeling like traps. Users see what went wrong, reach the right control without hunting, and complete the process without unnecessary friction. That is what accessible form validation looks like when it is built for production conditions instead of only passing a demo.

If your team needs clarity on where accessibility should live in your development process, or if responsibility is spread too thinly across roles, a structured strategy can bring confidence and sustainability to your efforts. At 216digital, we help organizations integrate WCAG 2.1 compliance into their development roadmap on terms that fit your goals and resources. Scheduling a complimentary ADA Strategy Briefing gives you a clear view of where responsibility sits today, where risk tends to build, and what it takes to move toward sustainable, development-led accessibility that your teams can maintain over time.