If you build modern interfaces, you probably lean on Flexbox, Grid, and positioning every day. With a few lines of CSS, you can rearrange entire sections, change layouts at different breakpoints, and keep one codebase working across phones, laptops, and large screens.

The downside is easier to miss: the more we shuffle things visually, the more likely it is that the visual order drifts from the actual HTML order and undermines accessibility. When that happens, people using a keyboard or screen reader can have a very different experience from what the design suggests. Focus jumps in ways they don’t expect. Announcements feel out of place. It becomes harder to stay oriented on the page.

For users who rely on assistive tech, it can feel disorienting when the page organization changes unexpectedly. “Next” may not always mean “next,” and navigating the page can require more effort to stay oriented.

This isn’t only a UX problem. It ties directly to WCAG 1.3.2 Meaningful Sequence and 2.4.3 Focus Order, which both expect content and focus to follow a logical, predictable path. That same alignment supports accessibility and reduces risk from a legal perspective.

In the rest of this article, we’ll look at how order breaks, where they tend to happen, and practical ways to design, test, and fix layouts so they stay flexible without becoming unpredictable.

Why Content Order Matters More Than It Looks

How Assistive Technologies See Your Layout and Accessibility

Screen readers don’t “see” layout. They move through the DOM in source order, using headings, landmarks, lists, and controls to understand how the page is structured. That’s the experience for someone listening linearly or jumping by element type.

Keyboard users follow the same underlying map. Each press of Tab moves through links, buttons, and form fields in DOM order, unless you’ve changed it with tabindex or custom scripting.

When the visual layout suggests one order and the DOM provides another, people feel things like:

- Focus jumping to unexpected areas.

- Content is being announced without a clear context.

- A mental model of the page that never really settles

Once trust is lost, every interaction requires more effort.

WCAG’s View: Meaningful Sequence, Focus Order, and Accessibility

Two Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) criteria are especially relevant:

- WCAG 1.3.2 Meaningful Sequence requires at least one programmatically determinable reading order that preserves meaning. If someone moves through the content in DOM order, it still needs to make sense.

- WCAG 2.4.3 Focus Order requires that focusable elements receive focus in an order that preserves meaning and operability. Keyboard users should not feel like focus is bouncing randomly around the page.

These expectations sit near the center of a solid accessibility approach.WCAG does not forbid visual rearrangement. It becomes a problem when the rearrangement changes how users understand the page or makes it harder to complete tasks. There can be more than one acceptable logical order, but at least one needs to be consistent and predictable.

The Human Impact Behind Accessibility

Behind these rules are people trying to do simple things: check an account, complete a form, submit a request.

Users with low vision or some cognitive disabilities may rely heavily on predictable patterns to stay oriented. They remember where search usually appears, where the main button usually sits, and how navigation is arranged.

Keyboard and screen reader users build similar expectations over time. When focus jumps in ways that don’t line up with what they see on screen, they lose confidence in the layout. Some keep going, slowly. Others stop and leave.

How CSS Reordering Breaks Reading and Focus Order

Common CSS Features That Can Disrupt Logical Order and Accessibility

Most order-related issues come from a small set of tools we use all the time:

- position: absolute or position: fixed, which pull elements out of normal flow

- The order property in Flexbox and Grid

- flex-direction: row-reverse and column-reverse

- Grid behaviors like grid-auto-flow: dense, line-based positioning, and grid-template-areas

These features are useful, and sometimes necessary. Problems begin when they’re used to fix hierarchy or flow rather than just adjust appearance.

What This Looks Like in Practice

Navigation Example

Say the DOM order for your navigation is: Home, Contact, About, Blog.

Design wants “Contact” on the far right, so you use order in a flex container to produce: Home, About, Blog, Contact.

Visually, this layout looks correct. However, for a keyboard user, pressing Tab navigates in the following order: Home, Contact, About, Blog. This means focus jumps from Home to Contact (on the far right), then back to About and Blog (toward the center).

This jump is unexpected, as nothing on-screen explains why the focus shifts. Screen reader users also hear a sequence that doesn’t match the visual layout, making navigation confusing.

Card Layout Example

You have a grid of cards, and you want a “featured” card at the top. Instead of moving it in the DOM, you position it using Grid placement or position: absolute.

On screen, it appears first. In the DOM, it still sits midway through the list. Keyboard and screen reader users only encounter it after several other cards, even though the design is signaling that it’s the main item.

Screen Readers and Flex/Grid Nuances

Different browser and screen reader combinations handle Flexbox and Grid differently. Some combinations try to align with visual order in certain situations; others follow DOM order strictly. That behavior can also change over time as engines evolve.

The safe rule is simple: treat DOM order as the source of truth. If the order matters to the user, fix it in the markup, not just in CSS.

Real-World Patterns Where Things Go Wrong

These patterns show up often in production interfaces and quietly cause accessibility problems if no one is watching for them.

Global Navigation and Utility Links

Common issues in navigation and headers include:

- Moving “Contact,” “Sign in,” or “Cart” to the far right using order or reversed flex directions

- Placing search or language controls visually near the top, but leaving them late in the DOM

Keyboard users end up with a navigation path that feels out of sync with what they see.

Hero Sections, Promos, and Feature Blocks

Hero areas and promotional content can introduce similar gaps:

- A main hero button that visually looks like the first action but appears later in the DOM

- Promotional banners positioned over content but rendered late, so focus reaches them long after users expect

Design signals one priority; source order signals another.

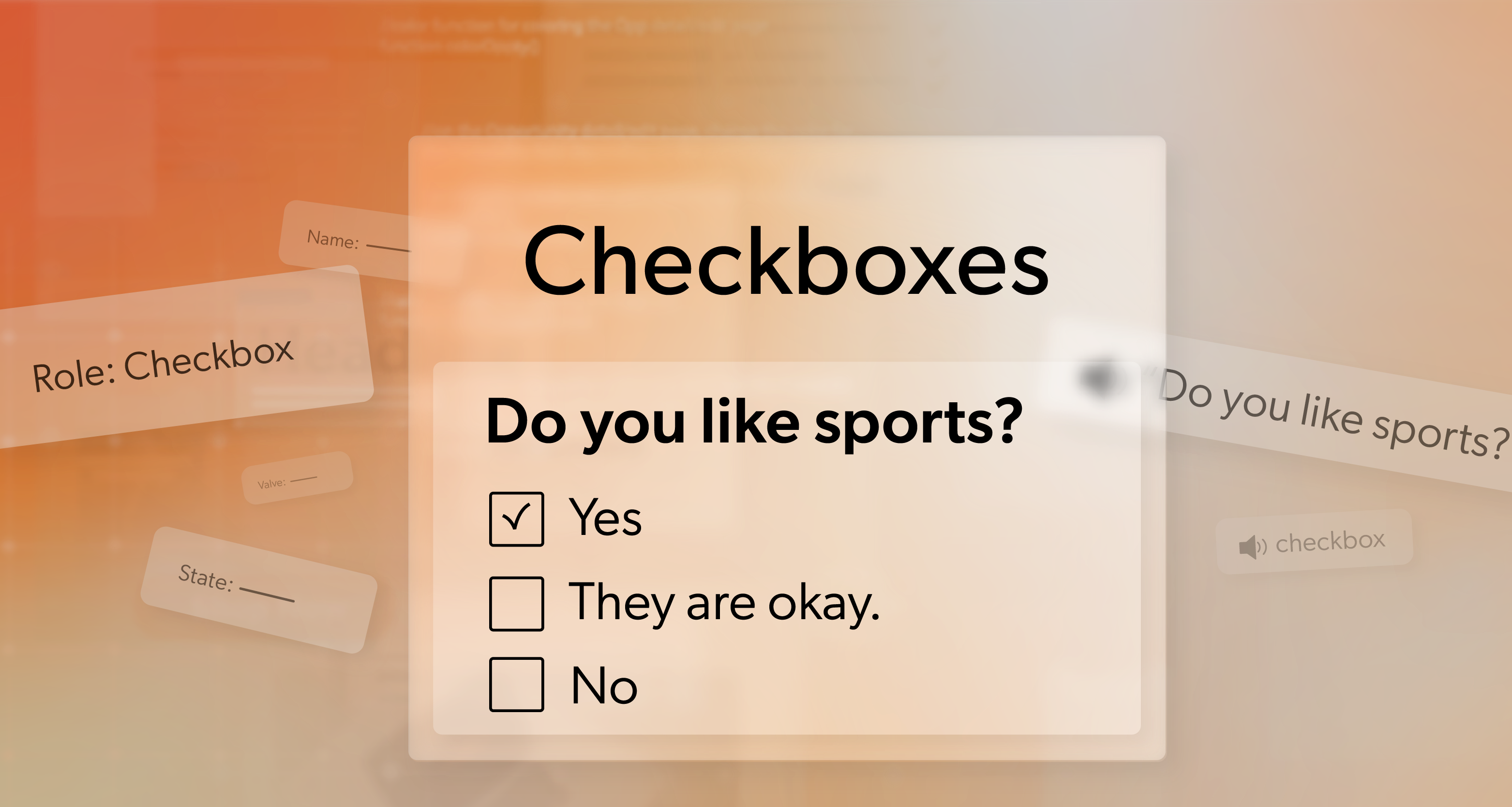

Forms and Multi-Column Layouts

Multi-column forms look neat, but they’re easy to misalign structurally:

- DOM order runs all the way down the left column, then all the way down the right, while the visual layout suggests row-by-row reading

- Error messages or helper text appear far from the related fields in the DOM.

Screen readers end up reading labels, inputs, and messages in a confusing sequence.

Dashboards and Responsive Grids

Dashboards and grid layouts bring their own risks:

- Drag-and-drop widgets change visual position, but the DOM order stays the same.

- Product or article grids change column counts across breakpoints, but the underlying order still reflects the original layout.

Sighted users see one arrangement; keyboard and screen reader users move through another.

Designing Layouts That Keep Source & Visual Order in Sync

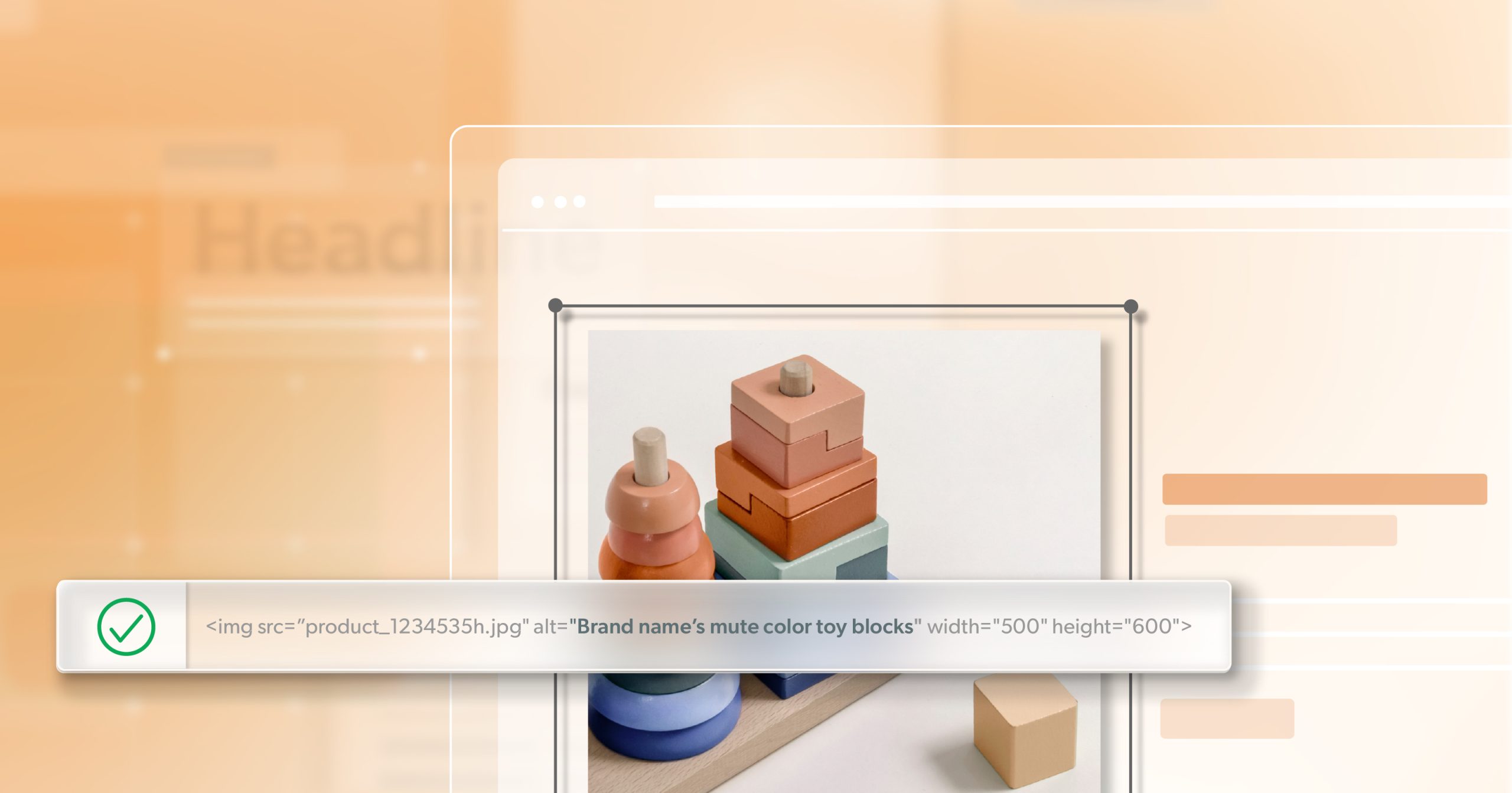

A helpful first check: if you remove all CSS, does the page still read in a sensible way from top to bottom?

Start with headings, landmarks, and content in a logical sequence. Use HTML elements that match their purpose, and add ARIA landmarks only when they’re truly needed. The better the structure, the easier everything else becomes.

Treat DOM Order as the Single Source of Truth

Set a clear expectation within your team:

If something needs to move for meaning or flow, change its position in the DOM instead of relying on visual reordering.

Reserve Flexbox/Grid order and absolute positioning for small visual refinements that don’t change the content’s meaning. When the markup matches the intended reading order, ongoing accessibility work stays much more manageable.

Mobile-First Thinking to Avoid Reordering Hacks

Designing from the smallest breakpoint forces you to decide what actually comes first in the linear flow. Once that order is set, larger layouts should build on it rather than fight it.

Instead of relying on row-reverse or heavy reordering to fix desktop layouts, adjust your HTML so each breakpoint builds on the same clear sequence.

When Visual and Logical Order Can Safely Diverge

There are places where visual and DOM order can differ without causing issues, such as:

- Independent articles or cards that don’t depend on each other

- Decorative elements whose position doesn’t change the meaning or task flow

Even there, keep focus order predictable within each unit and keep related elements together.

Responsive Design and the Reordering Trap

Responsive layouts often move panels around: sidebars shift from right to top, filters move above or below results, utility sections change position as the screen shrinks.

If those changes are made only with Flexbox or Grid reordering rather than structural changes, keyboard focus and reading order can feel out of sync with the visual layout. Over time, that chips away at accessibility across breakpoints.

Strategies to Avoid Paint-Over Layouts

A few practical habits help here:

- Prefer stacking and modest visual shifts over large reordering jumps.

- Decide early how content should flow linearly as the viewport changes.

- When you do reorder at a breakpoint, test that view with keyboard and assistive tech, not just by eye.

Emerging Tools: reading-flow and Future Support

New CSS features like reading-flow (currently available in some browsers) aim to align reading and focus order with visual order in flex, grid, and block layouts.

They’re promising, but support is still evolving. Treat them as enhancements, not a replacement for a clean structure. A clear DOM order will remain the more stable foundation.

Testing Reading and Focus Order in Everyday Workflows

Keyboard-Only Walkthroughs

One of the simplest and most useful tests is to set the mouse aside and use only the keyboard.

Tab through navigation, search, forms, checkout, and key dashboards. Watch for:

- Focus landing in unexpected places.

- Important elements are being skipped.

- Visible focus not matching what you would expect to come next.

This kind of quick check catches many accessibility issues long before formal testing.

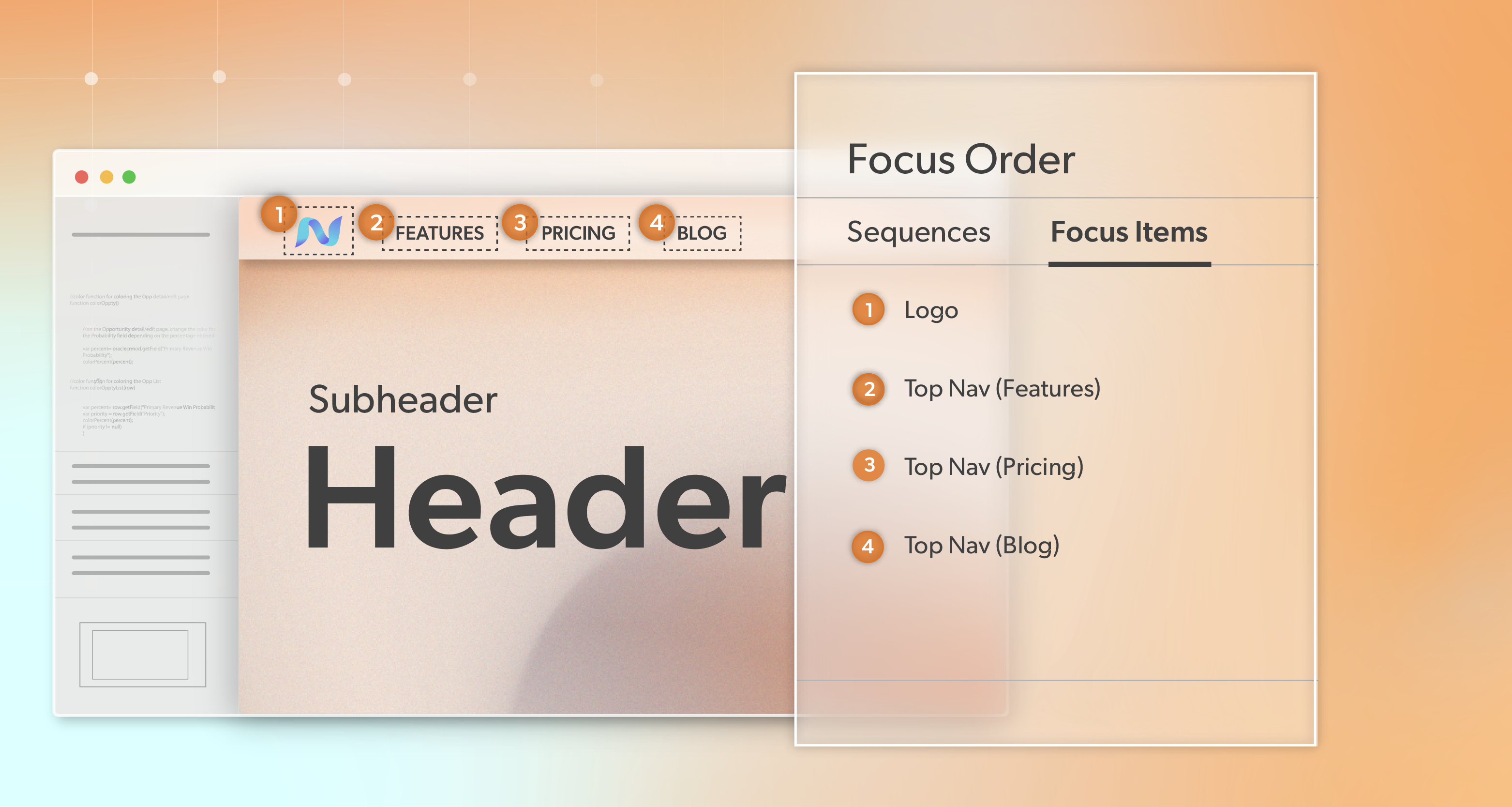

Using Tools to Visualize Tab Stops and Sequences

There are tools and browser extensions that overlay numbers and lines to show the actual tab sequence. They make it easy to see when Flexbox, Grid, or positioning has produced a focus path that doesn’t match the design.

Adding these checks to regular QA is more effective than treating them as a one-time audit.

Screen Reader Spot-Checks

Short passes with a screen reader are also valuable. With NVDA, VoiceOver, or another option, move through key flows and confirm:

- Headings and regions follow a logical sequence.

- Instructions, labels, fields, and messages appear together in a sensible order.

Structural Smoke Tests in the Browser

For a quick structural check, temporarily disable CSS in dev tools or with an extension, then read the page in DOM order.

If it still makes sense, you likely have a solid base. If not, you’ve found a structural problem that is worth fixing before it spreads.

Fixing Existing Interfaces Without Starting From Scratch

Prioritize High-Risk Flows First

You don’t need to refactor everything at once. Start where order matters most:

- Global navigation

- Sign-up and sign-in flows

- Checkout and payment

- Important forms and dashboards

Compare how the layout looks with how keyboard focus and reading order actually move, and note the mismatches that affect meaning or task success.

Refactor Layouts to Respect Source Order

From there, adjust markup so the DOM reflects the intended order:

- Move sections in the HTML so they match the intended sequence.

- Group labels, fields, and messages together

- Replace heavy CSS-based reordering with patterns that rely on better structure.

This improves usability and gives you a more predictable layout to maintain long-term accessibility.

Bake Order Rules Into Your Design System

Your design system is a good place to codify these expectations:

- The visual and DOM orders should match by default.

- Exceptions must be documented and tested.

- Core layout components for nav, cards, and forms should ship with safe reading and focus patterns built in.

Continuous Improvements, Not One-Off Accessibility Cleanup

Order and focus shouldn’t be left to occasional audits. Add a few simple checks to code review:

- Does tab order match what we see?

- Are we using order, row-reverse, column-reverse, or absolute positioning in ways that might change meaning?

Where it fits, linting or CI rules can also flag risky layout patterns early.

Source Order: The Thing You Can’t Fake With CSS

When visual layout and DOM order stay aligned, interfaces feel calmer and easier to use. People can trust that what they see on screen matches what their keyboard and tools will encounter.

Small structural decisions—good HTML order, clear roles, careful use of layout features—can make a noticeable difference in both user experience, accessibility, and compliance.

If your team is planning a redesign, cleaning up legacy layouts, or just trying to understand where to focus first, you don’t have to figure everything out alone. An ADA-focused briefing with 216digital can help you map out your highest-impact order issues, connect them to legal risk, and build better habits into your ongoing design and development work.

When you’re ready, setting up that conversation can give your next release cycle a stronger foundation—visually, technically, and legally.