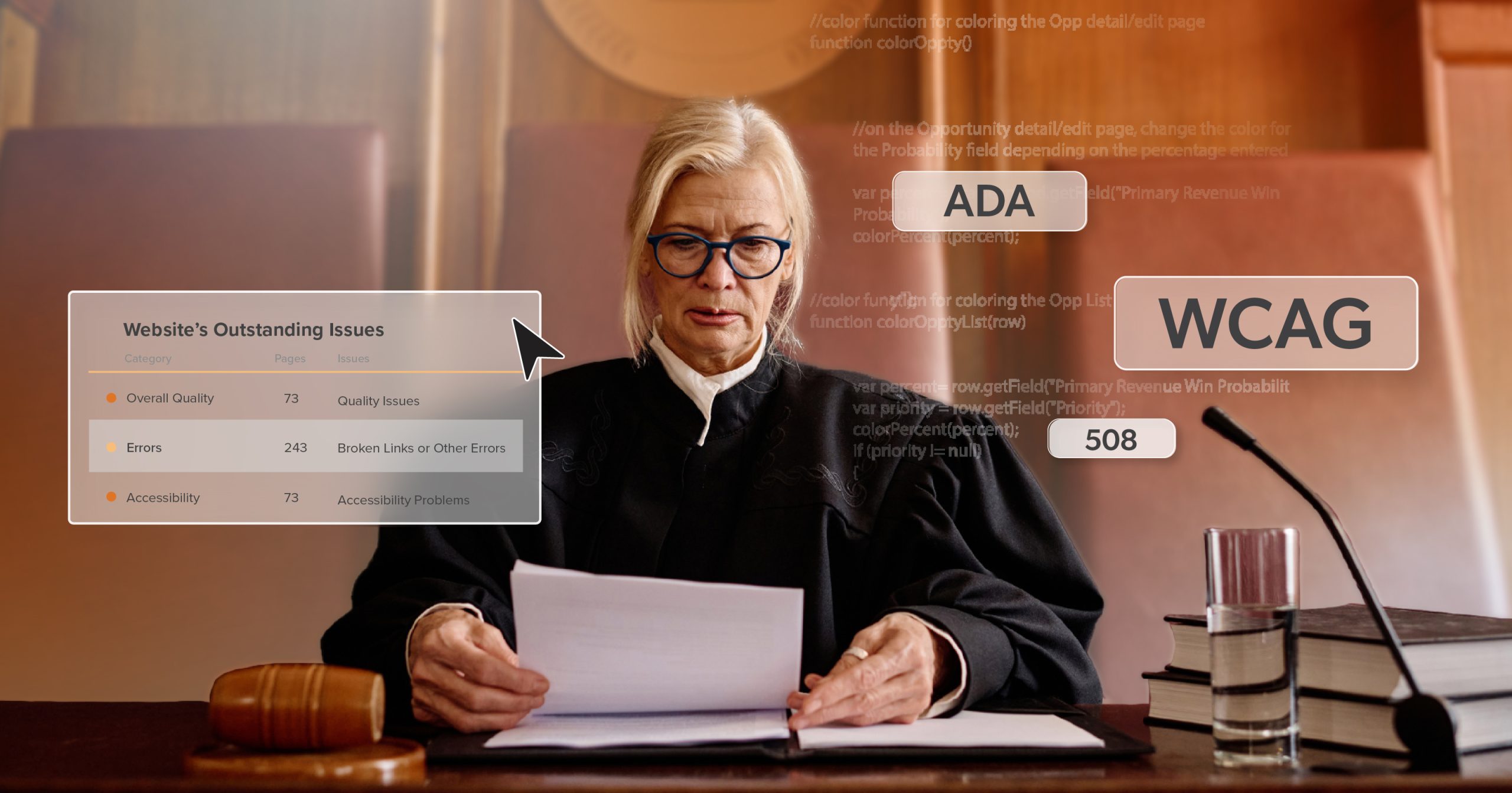

Many business owners feel caught in the middle of the rising wave of digital accessibility lawsuits. They may care about access and want to do the right thing, but they also face unclear expectations, inherited platforms, limited resources, and legal threats that arrive with little warning. One week you are focused on running the business. The next, you are triaging risk, trying to understand what went wrong, and figuring out what you can realistically fix and how fast.

H.R. 7668, also known as the ADA 30 Days to Comply Act, is getting attention for that reason. It proposes a notice-and-cure process for certain ADA Title III claims, giving businesses a short window to address reported barriers before a lawsuit can proceed. If you have already faced multiple claims, or you are worried about being targeted next, that window can sound like overdue breathing room. More time to fix. Less pressure to settle.

The catch is what happens during that waiting period, and who pays the cost of the delay. On the web, access often means completing something time-sensitive. A job application, a class registration, a patient portal, a government form, a purchase. This article breaks down what H.R. 7668 would change, why many businesses support it, why advocates see risks, and what actually helps reduce exposure to ADA website lawsuits while still moving accessibility forward.

What H.R. 7668 Would Change

At the center of H.R. 7668 is a notice requirement and a short remediation window before a civil action may be filed under Title III. The proposal is commonly referred to as the ADA 30 Days to Comply Act.

In practical terms, it would require a person to notify a business of an alleged accessibility barrier and give the business 30 days to address it before filing a Title III lawsuit. This could change the timing of ADA Title III website lawsuits by adding a notice step before filing.

Supporters often describe it as a common-sense fix. Many businesses feel they are hit with legal pressure before they even understand what the problem is. They want a chance to respond without being forced into a quick settlement that does not always lead to lasting improvements.

At the same time, digital access is often time-sensitive. If someone cannot apply for a job, complete coursework, access healthcare information, or use a government service when it matters, waiting can mean the opportunity is gone. That tension shows up quickly once the conversation shifts from legal process to real usage.

Why Web Accessibility Issues Repeat

A notice-and-cure approach assumes a business needs a heads-up before it can act. Sometimes that is true. A missing label, a broken link, or an overlooked content update can happen.

But many web accessibility issues repeat because the source is shared.

- A page template has an incorrect heading structure, and that template drives most pages on the site.

- Buttons are built as non-button elements, so keyboard users hit the same wall across menus, filters, and modals.

- Form errors are shown only with color, and the same form pattern is reused in many places.

- A third-party tool is added without testing, then becomes required for checkout, scheduling, or account access.

- New content is published quickly, but the workflow does not include checks for alt text, table structure, or captions.

When issues keep repeating, notice is not the missing piece. A working process is.

This is also where timelines get tricky. If the barrier is tied to a design system or a CMS theme, remediation is not one edit. It can mean code changes, content revision, QA, and sometimes vendor coordination.

Why Businesses Support 30 Days to Comply

Supporters of the ADA 30 Days to Comply Act often frame the 30-day window as basic fairness and focus. Many organizations do not have in-house accessibility expertise. They are juggling older platforms, third-party tools, and competing priorities. When a lawsuit lands first, costs often go to legal defense and settlement pressure instead of to remediation. A notice-and-cure requirement, in that view, creates breathing room so dollars can go toward fixing barriers instead of quick payouts.

That argument is also tied to what the lawsuit data shows about repeat targeting. Of the more than 5,000 digital accessibility lawsuits filed in 2025, 1,427 targeted companies that had already faced an ADA web accessibility claim. In federal court alone, 46 percent of cases involved repeat defendants. Plaintiff firms track litigation history and revisit companies targeted previously for easy wins. When businesses see that cycle, it is easy to understand why some view a portion of filings as driven by litigation incentives rather than by a push for durable accessibility.

It is worth saying clearly that many lawsuits are brought by individuals with disabilities, raising legitimate access barriers. That is part of why this space is so serious. The concern from businesses is that repeat targeting can turn into a pattern where the money goes to settlements instead of fixes, and the underlying site stays vulnerable.

That is the business-side hope behind H.R. 7668. Delay litigation long enough to put resources into remediation first. Bring the focus back to what matters. A site people can use.

Why Advocates Oppose Notice-and-Cure

The civil rights concern does not disappear because repeat filings exist. Notice-and-cure requirements still place the first step on the person who hit the barrier, and that person still experiences the impact in the moment.

If someone cannot complete a time-sensitive task, a 30-day wait can function like a closed door. Even if the site is improved later, the missed opportunity does not come back. That is why disability advocates push back on any model that makes access contingent on a complaint-first process.

This is the tension the ADA 30 Days to Comply Act puts in sharper focus. Businesses want a fair chance to direct resources toward remediation instead of settlements, especially when they fear repeat targeting. People with disabilities need usable access when they arrive, not weeks later.

If policy changes move forward, the measure of success should be practical. Fewer barriers. Faster fixes that hold up over time. Less repeat litigation because the underlying issues were actually addressed.

Pros of the ADA 30 Days to Comply Act

There are situations where notice-and-cure could lead to better outcomes, especially for teams that are willing to act quickly and work on root causes.

- Reduces the rush to settle, giving teams room to invest in fixes.

- Creates a clearer internal trigger for action, especially in organizations where accessibility keeps getting postponed.

- Encourages faster response when barriers are limited, and the team can move quickly.

- Builds public trust when an organization responds with transparency and follow-through.

A notice window can be useful when it leads to real remediation and better practices afterward. The risk is when it becomes a timing shield instead of a change in behavior.

Cons of the ADA 30 Days to Comply Act

Even teams acting in good faith can run into problems with a 30-day cure period, especially in digital systems with complexity and volume.

First, it can increase the number of formal notices. If notice becomes the required entry point, more people will use it. That does not automatically mean bad intent. It can simply reflect the new process.

Second, thirty days can be tight for web remediation. Many issues do not live in one place. Navigation, forms, checkout, account access, PDFs, video libraries, and third-party tools can all be part of the claim. Fixing those well takes planning and testing.

Third, rushed fixes can backfire. A patch on one page does not help if the same component appears across the site. When teams fix symptoms instead of shared patterns, problems return on the next release.

And finally, legal exposure does not disappear. A notice step changes the timeline. It does not remove the obligation. If barriers remain, or if the response is incomplete, litigation can still follow.

This is why H.R. 7668 does not eliminate risk. It changes how the first phase may unfold.

How to Reduce ADA Website Lawsuit Risk

Policy debates tend to focus on process. Lawsuit prevention tends to come down to outcomes. The most reliable way to reduce web accessibility lawsuits is to reduce barriers.

That does not require perfection. It requires repeatable habits that hold up through releases and content changes.

A strong foundation usually includes:

- Clear design and development standards aligned with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

- Manual testing paired with automated checks

- A review step that happens before release, not only after complaints

- Content rules that help editors publish accessibly by default

- Review of third-party tools before they become part of critical tasks

- Ownership and documentation so that fixes do not drift between teams

When those pieces exist, accessibility work stops feeling like an emergency cleanup. It becomes maintenance and quality control. That is also when budgets and timelines become more predictable, and repeat issues start to drop.

This is also where web accessibility compliance becomes more predictable. When accessibility is built into design, development, and publishing, it stops being an emergency project and becomes part of quality control.

Whether the ADA 30 Days to Comply Act passes or not, that approach protects users and lowers exposure.

What to Do If You Get an ADA Notice

If a notice-and-cure structure becomes the norm, response quality will matter. Panic leads to shortcuts, and shortcuts create repeat problems.

A practical response plan often looks like this:

- Acknowledge quickly and document everything.

Confirm receipt. Log dates. Keep communication in one place. - Validate what is being alleged.

Some claims are accurate. Some are incomplete. Testing helps separate the two. Manual checks matter here. - Prioritize critical user journeys first.

Focus on the paths people need to complete tasks. Navigation, forms, checkout, account access, and core conversions usually come first. - Fix at the source when possible.

If the issue is in a shared component, fix it there. If content is involved, adjust the workflow so the issue does not keep spreading. - Track progress with evidence.

Save tickets, notes, test results, and before-and-after examples. Good records support good faith and reduce confusion later.

A 30-day window can help teams move quickly. It can also expose teams that lack a plan. Either way, being prepared tends to reduce cost, stress, and repeat risk.

Notice-and-Cure and the Future of ADA Website Claims

H.R. 7668 and the ADA 30 Days to Comply Act are often framed as a way to reduce bad-faith lawsuits and give businesses time to fix issues instead of paying settlements. That concern is worth taking seriously, especially when repeated targeting appears in the data.

At the same time, digital access is time-sensitive. Delays can mean missed opportunities and exclusion, even when fixes come later. That is why this proposal draws strong opinions on both sides.

The clearest path forward is still the same. Build accessibility into how websites are designed, developed, and maintained. Reduce barriers at the source. Make fixes that hold up across releases.

That kind of progress is easier to sustain when WCAG 2.1 compliance work is tied directly to the development roadmap, with clear priorities and ownership. If support is needed to build that strategy, 216digital can help you do it on your terms. Schedule a complimentary ADA Strategy Briefing and let’s build a path that supports both business goals and user needs.